From: Power of Patients Spring Blog

A traumatic brain injury affects more than just you and your brain. It affects everyone who comes in contact with a person suffering from a TBI.

It makes sense that an injury to the brain would affect brain processing as well as motor skills. But does TBI affect emotions?

Studies and anecdotal evidence together, indicate that TBI and anger go hand in hand, not just because of the injury to the emotional center of the brain, but because of the frustration that comes with recovering from a traumatic brain injury.

Over 70 percent of families of individuals with a TBI report the TBI victim demonstrating irritability and anger.

Keep reading for a full explanation of how a traumatic brain injury causes anger and irritability, and what both caregivers and victims can do when anger begins to bubble up.

What is a Traumatic Brain Injury?

A traumatic injury is more than just a general bump on the head. A TBI is the result of a violent blow to the head. It is a permanent injury to the brain.

Individuals can also suffer from a TBI if matter, such as a shattered piece of skull bone or a bullet, goes through the brain.

Major and mild traumatic brain injuries will affect the brain differently. A mild TBI may cause temporary damage. A serious TBI, on the other hand, can result in permanent damage to the brain and possibly death due to long-term complications.

Why does a TBI Cause Irritability and Anger?

The different reactions to a TBI stem from a variety of reasons. For example, men and women respond differently to a TBI. Women tend to respond to a TBI with depression, substance abuse, and memory problems, whereas men struggle with more irritability and depression.

Thus, first, you need to consider the gender of the individual suffering from a TBI. No two people will respond the same.

With that said, many individuals with a TBI demonstrate a shorter fuse than the average person. They have quick tempers and tend to fly off the handle frequently. They may use course language, slam their fists into things, threaten the people they love, slam doors, and throw objects.

The TBI causes irritability and anger when the injury affects the limbic system of the brain. This part of the brain is responsible for emotional responses as well as hormone release, sexual responses, and temperature regulation.

Thus, when your limbic sy stem sustains a traumatic injury, it only makes sense that you will have a difficult time controlling your emotions. You may find yourself irritated by small things or angry over things that would not have bothered you in the past, simply because your brain is not functioning as it did before your injury.

stem sustains a traumatic injury, it only makes sense that you will have a difficult time controlling your emotions. You may find yourself irritated by small things or angry over things that would not have bothered you in the past, simply because your brain is not functioning as it did before your injury.

Other Potential Causes

When you suffer from a TBI, you may have a difficult time controlling your temper. This difficulty stems from more than just the actual brain injury.

It could also stem from simple frustration or dissatisfaction with the new life you have to live. Your traumatic brain injury could be causing motor deficiency and physical changes. You could feel frustrated with these changes.

Often, individuals with a TBI will feel isolated and misunderstood. No one other than other people with a TBI understands what they’re going through. As a result, they may feel depressed, as well as angry.

A TBI can affect attention span as well as memory. As a result, individuals with a TBI may experience difficulty concentrating and remembering things. This challenge can lead one to become frustrated and angry.

Individuals with a TBI will also tire more easily. When you tire easily, you miss out on important parts of life, and this can be frustrating, too.

What the Anger Looks Like

These mitigating factors can all lead to anger that will look the same, regardless of the factors that cause it. One thing is certain. The anger expressed by someone with a TBI often stems from several causes in combination and not just one single thing.

For example, when you suffer from a TBI, you may lose your job and financial stability. You may feel like you’ve completely lost control over your life. These losses will lead to both sadness and anger, especially since the TBI stems from something completely out of the victim’s control.

Some people already had an anger problem before their TBI. The TBI will just exacerbate an issue that existed before the injury.

However, some individuals will develop impulsive anger. They will just snap suddenly and seemingly without any cause.

There is a physiological cause, though. Often these individuals have suffered brain damage to the part of the brain that would normally inhibit angry feelings and the behavior that accompanies them. In a normal brain, when a person feels anger, a part of the brain will stop that individual from acting on the anger.

For an individual who has had a TBI, though, the brain will not stop the anger because it has sustained damage. As a result, they will respond quickly and severely in anger in a way that they normally would not have behaved before their injury.

Impulsive anger makes itself known through a few different symptoms:

- The individual did not demonstrate the same type of anger before the injury

- The angry feelings appear and leave suddenly

- Minor events precede the angry episodes

- The individual who demonstrates quick anger also feels embarrassed or surprised when it happens

- Physiological stress such as pain, low blood sugar, or fatigue worsens the anger

These symptoms may indicate a type of anger that the TBI has caused.

Irritability and Anger Triggers

Once patients and caregivers determine that a traumatic brain injury has caused a problem with anger, they can begin to determine the triggers that lead to the angry outbursts.

While each brain injury survivor responds differently to their TBI, there are some common factors in most survivors.

The brain injury survivor is, in some ways, a different person. What makes them angry may be different. We need to learn what those things are. Here are some common factors that contribute to anger after a brain injury.

Factors that Lead to Angry Outbursts

Environmental factors, as well as personal factors, can stimulate an angry outburst. Here are a few of the most common factors that lead to a person snapping:

- High activity level

- High noise level

- Unexpected changes in schedule

- Lack of structure and unpredictability

- Fear and anxiety

- Embarrassment

- Shame

- Guilt

- Frustration

- Memory deficits

- Communication deficits

Physiological factors can also lead to angry outbursts. For example, low blood sugar leads the average person to become “hangry.” Someone with a TBI will feel extreme levels of anger when their blood sugar dips.

Here are a few other physiological causes:

- Physical pain

- Wrong levels of medication

- Fatigue

- Drugs

- Alcohol

These physiological factors would lead the average person to feel irritated. But the average brain can also stop the angry outburst. An individual with a TBI does not have that capacity.

Signs Before The Outburst

When you know what to look for, you can prevent an angry outburst. The impulsive anger demonstrated by someone with a TBI differs from the average person with a few different physiological, speech, and behavioral signs. Here are the most common signs:

- Threatening speech including cursing and name-calling

- Loud voice

- Clenched fists

- Increased fidgeting and movement

- Throwing and breaking items

- Physical violence

- Racing heart

- Sweating

- Clenched muscles

- Bulging eyes and flushed face

- Increased breath rate

Additionally, providers that work with TBI patients will notice mental signs such as feelings of fear or anxiety, embarrassment, hurt, shame, guilt, and frustration.

While all of these symptoms are common with individuals that do not have a TBI, when a person encounters a situation that makes them angry, those with a TBI will demonstrate the signs at times that simply do not make sense.

Treating and Managing a TBI

Providers working with an individual that has suffered from a TBI can limit angry outbursts with the right preventative and management techniques. Consider the triggers that could lead to an angry outburst, and then avoid those triggers. Here are a few basic ideas.

Create a Safe Environment

You can create a safer environment by removing potential weapons as well as drugs and alcohol. Keep both dangerous tools and vehicles inaccessible as well.

Regulate Stimulation

Test and know the individuals you’re working with. Some people with a TBI need to avoid overstimulation, so have dimmer lights and calm colors. Other individuals will need distractions and busyness, so plan for them accordingly.

You will also want the right amount of supervision for that individual. Create the least restrictive environment while still creating a safe environment.

If that individual struggles with orientation, be prepared to redirect them regularly, reminding them of where they are and what is happening.

Give Space

It’s alright to withdraw from the individual to give them a chance to cool down. Sometimes the person in the middle of an angry outburst just needs space and time, so give it to them.

Re-Focus

Guide the individual to gather themselves by changing the subject and helping them focus away from whatever has made them angry.

Regulation Strategies

Once a brain-injury survivor has recovered physically, you can begin to teach them methods that will help them learn how to deal with the overwhelming feelings of anger that assault them. Here are a few common strategies.

Retreat

When the individual begins to feel the anger bubble up, they need to look for a physical way out. It’s okay to retreat. At the beginning of teaching this technique, caregivers will want to teach the individual a cute word or symbol that lets that person know they’re about to go over the edge.

At some point, the individual will learn to recognize their physiological symptoms and then self-regulate by removing themselves from the situation.

Mental Break

If a physical retreat isn’t an option, the individual should use mental techniques that allow them to calm down. You can teach them to take a deep breath, close their eyes, and then take another big breath.

Other factors will help with calming down, such as prayer, meditation, soft music, and even physical exercise.

Prepare, Then Come Back

Before the individual brings themselves back to the situation that has caused anger, they need to review some basic questions. Have the individual with a TBI practice and use these questions.

- Should I apologize?

- Should I explain my absence?

- Should I share my feelings with anyone?

- How can I avoid this problem in the future?

The answers to these questions will allow the individual with a TBI to return to the situation and build relationships despite their disability.

All of these techniques combined will help the individual with the TBI to recognize their problems, handle them, and maintain meaningful relationships in society.

Education and Action for TBI Victims

Anyone who experiences irritability and anger runs the risk of ostracizing their loved ones. There is a way to deal with a TBI, though, that allows one to have meaningful relationships.

First, the individual must note why they’re angry. Once they’ve recognized their triggers, they can either avoid them or learn how to manage them. By following some basic steps, they can move their way back into society and friendships that last a lifetime.

Have you suffered from a brain injury or know someone that has? Do you work with TBI survivors? If so, we can help you.

We have designed an app with an easy-to-use dashboard to help brain injury patients and their caregivers. By using Sallie, our FREE, customized app, you can track these symptoms and triggers that cause your irritability.

Tracking this information with our app lets you manage your brain injury better. Thus, you can show your data to any provider that can further help you manage your TBI.

We aim to empower patients and caregivers with data and drive change, to reshape and accelerate clinical trials which help people who suffer from brain injuries.

Check us out today. We have some personal connections that drive our passion to help individuals with brain injuries.

Works Cited:

https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/get_the_facts.html

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/traumatic-brain-injury/symptoms-causes/syc-20378557

https://msktc.org/tbi/factsheets/emotional-problems-after-traumatic-brain-injury

https://www.healthline.com/health/what-part-of-the-brain-controls-emotions

https://www.powerofpatients.com/blog/the-differences-between-males-and-females-with-brain-injuries

https://www.powerofpatients.com/about

https://www.powerofpatients.com/providers

https://www.powerofpatients.com/patients-caregivers

Photo sources from ScienceNews for Students

Photo sources from ScienceNews for Students

stem sustains a traumatic injury, it only makes sense that you will have a difficult time controlling your emotions. You may find yourself irritated by small things or angry over things that would not have bothered you in the past, simply because your brain is not functioning as it did before your injury.

stem sustains a traumatic injury, it only makes sense that you will have a difficult time controlling your emotions. You may find yourself irritated by small things or angry over things that would not have bothered you in the past, simply because your brain is not functioning as it did before your injury.

Photo of

Photo of

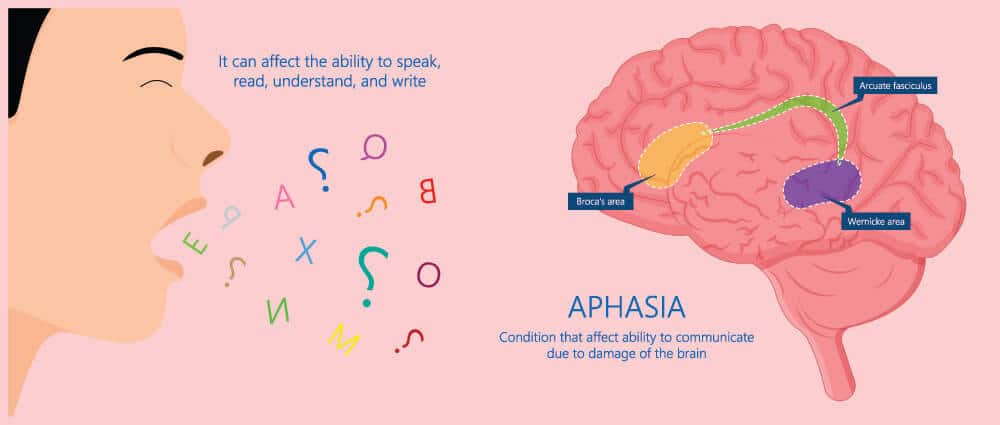

lot in the hospital after a stroke or brain injury. Medical professionals tend to describe aphasia to the families as receptive aphasia, expressive aphasia, or mixed aphasia. This is a generic label families hear early in the recovery process.

lot in the hospital after a stroke or brain injury. Medical professionals tend to describe aphasia to the families as receptive aphasia, expressive aphasia, or mixed aphasia. This is a generic label families hear early in the recovery process.